Scottish independence

| Scotland |

.svg.png) This article is part of the series: |

|

|

Scotland in the UK

Scotland in the EU

Local government

|

|

Other countries · Atlas |

Scottish independence is a political ambition of political parties, advocacy groups and individuals for Scotland to secede from the United Kingdom and become a sovereign state, separate from England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Kingdom of Scotland was an independent state from its own unification in 843. Though it was largely conquered in 1296 by Edward I of England, resistance continued until Scotland regained de facto independence after defeating English forces at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. England finally acknowledged Scottish independence with the signing of the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton in 1328. The crowns of England and Scotland were united by the accession of James VI to the English throne in 1603; however Scotland remained a sovereign and officially independent realm until 1707 when the Treaty of Union was passed by the Parliament of Scotland which created the unified Kingdom of Great Britain and Scottish sovereignty ascended to the new state. The Acts of Union that put the Treaty into effect provided for the merging of the two nations by means of dissolution of the Parliament of Scotland and the Parliament of England and their replacement by a new Parliament of Great Britain located in Westminster, England. As a result of provisions in the Treaty, as well as much of Scotland's relative isolation, many of Scotland's institutions remained separate and the Scottish national identity has remained strong and distinct.

At the time of the union of the parliaments, the measure was deeply unpopular in both Scotland and England.[1] The Scottish signatories to the treaty were forced to sign the documents in secrecy because of mass rioting and unrest in the Scottish capital, Edinburgh.[2]

Supporters of Scottish independence believe that the loss of independently Scottish representation internationally is detrimental to Scottish interests, and that as the British government acts primarily in the interest of the entire United Kingdom, they believe it can be, in specific instances, to the inadvertent, perceived or deliberate detriment of specifically Scottish interests. Those who oppose Scottish independence and endorse the continuation of a form of union make a distinction between nationalism and patriotism, believing being part of the United Kingdom to be in the Scottish national interest, and arguing that cultural, social, political, diplomatic and economic influence and benefits enjoyed by Scotland as part of a great power, without compromising its distinctive national identity, outweighs the loss of fully independent Scottish sovereignty.

Contents |

History

Early formation and Wars of Independence

The Kingdom of Alba first emerged as a unified nation state in 843, with its capital at Scone, under the rule of King Kenneth I, who as ruler of the Gaelic Kingdom of Dál Riata led a conquest of the Pictish kingdom Fortriu and later kings expanded their territories to control parts of the Brythonic Kingdom of Strathclyde and the Anglian Kingdom of Northumbria after the Battle of Carham. A similar process of amalgamation also came about in the South of Great Britain with the formation of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, that developed into the neighbouring Kingdom of England. The border between the two states was eventually formalised by the Treaty of York in 1237. The Kingdom of Scotland further expanded with the signing of the Treaty of Perth with Norway in 1266, although Orkney and Shetland would remain under Norwegian rule until 1468.[3] A reliance on sea trade led to close links with the Baltic states, the Low Countries, Ireland and France. A crisis of succession in 1290 severely weakened Scotland and led to an opportunity for the neighbouring English king, who had recently conquered the Welsh Kingdoms, to further consolidate his rule over the whole of Great Britain. Edward I of England invaded Scotland in 1296 and was initially successful in subduing much of Scotland. However, Edward died in 1307 and Scottish troops under the command of King Robert I began waging a war of liberation. Initially employing guerrilla tactics that were pioneered by William Wallace,[4] Robert was enormously successful and strengthened his position as king, although he was still fighting a de facto civil war against supporters of his murdered rival John Comyn, who were eventually defeated at the Battle of Inverurie in 1308. In 1314 Edward II sent a large English army to quell the Scottish rising political power. However, Edward's superior army was routed at the Battle of Bannockburn. King Robert had won a decisive victory and Scotland secured its independence.[4] Six years after the Battle, in 1320, the Declaration of Arbroath was sent by the Scottish nobility to Pope John XXII. The declaration rejected the claim of the kings of England to the Scottish throne and also emphasised the priority of the entire Scottish nobility over the authority of any single monarch in maintaining independence.[3] One passage in particular is often quoted from:

- ...for, as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom – for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.[5]

England eventually recognised Scottish independence in the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton. After the death of Robert the Bruce however, Edward Balliol and his supporters renewed the rival claim to the throne and counted on English support, which culminated in an English invasion in 1332, sparking the Second War of Scottish Independence. The English took Berwick-upon-Tweed after the Battle of Halidon Hill but this war coincided with the Hundred Years' War, and eventually England became preoccupied with this cause. Bruce's son, David II of Scotland acting in support of France in the Auld Alliance was taken prisoner at the Battle of Neville's Cross in 1346 after his disastrous invasion of England, and was only released eleven years later in 1357, after the Parliament of Scotland agreed to pay a 100,000 Marks ransom in the Treaty of Berwick, which also marked the last attempt by the Kingdom of England to directly interfere in the Scottish succession. Berwick-upon-Tweed itself, remained a disputed territory between England and Scotland, resulting in the Anglo-Scottish Wars, which involved battles such as the Battle of Otterburn, Battle of Nesbit Moor and the Battle of Humbleton Hill, until the eventual signing of the Treaty of Perpetual Peace in 1502. This treaty was also later broken however, with Scotland's invasion of England, again as part of the Auld Alliance, in the War of the League of Cambrai in 1513, culminating in the Battle of Flodden Field. A further war with England broke out under King James V with the Battle of Haddon Rig and Battle of Solway Moss in 1542. After the King's death, and the coronation of Mary, Queen of Scots, the first proposal for a Union of the two Kingdoms was raised in the Treaty of Greenwich, which itself ultimately led to further conflict in The Rough Wooing. The last pitched battle to be fought between the Kingdoms of Scotland and England was the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh in 1547.

Union of the Crowns

In 1603 King James VI of Scotland inherited the throne of England (as King James I), after the death of Queen Elizabeth I, and thus "united" Scotland and England under a single monarch.[3] The term "united" itself, though now generally accepted, is misleading; for properly speaking this was merely a personal or dynastic union, the crowns remaining both distinct and separate. Despite James' best efforts to create a new Kingdom of Great Britain,[6] England and Scotland continued to be resolutely independent states, maintaining independent parliaments and governments.

The new king was initially popular in England as a ruler who already had male heirs waiting in the wing. But James' honeymoon was of very short duration; and his initial political actions and belief in the Divine Right of Kings were to do much to create a rather negative tone. The greatest and most obvious of these was the question of his exact status and title. James intended to be King of the entire British Isles, exemplified in his commission of the Union Flag.[6] His first obstacle in this imperial ambition however was the attitude of the Parliament of England which opposed the loss of England's independence.[7] In Scotland the union desired by James met with the same lack of zeal that it did in England.[6]

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

After the execution of King Charles I the previous year, in 1650, part of the English Parliament's New Model Army invaded Scotland to fight Scottish Covenanters at the start of the Third English Civil War. The Covenanters, who had fought against the Crown during the Bishops' Wars and had been allied to the English Parliament in the First English Civil War, had crowned Charles II as King of Scots. Despite being outnumbered, Oliver Cromwell led the Army to crushing victories over Charles's Scottish army commanded by David Leslie at the battles of Dunbar and Inverkeithing. Following the Scottish invasion of England led by Charles II, the New Model Army and local militia forces soundly defeated the Royalists at the Battle of Worcester, the last pitched battle of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. During the Interregnum, Scotland was kept under the military occupation of the New Model Army under George Monck. They were kept busy throughout by the Royalist rising of 1651 to 1654 in the Scottish Highlands and by endemic lawlessness by bandits known as mosstroopers. The Commonwealth of England and later The Protectorate imposed a brief Anglo-Scottish parliamentary union from April 1652, however, the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 saw the return of Scottish autonomy in the Parliament of Scotland.[8]

Treaty of Union

Once the terms of the Treaty of Union were agreed, the Scottish and English Parliaments passed Acts of Union (England in 1706 and Scotland in 1707) to put the provisions of the Treaty into effect and create a Political union. Both the Scottish and the English Parliaments were dissolved, and all their powers were transferred to a new Parliament of Great Britain located in the largest city in the new United Kingdom, London. Certain significant matters remained separate, including Scots law, the Burgh system, education in Scotland, the Church of Scotland and the Order of the Thistle. Most aspects of Scottish culture and Scottish national identity remained strong and distinct.[9]

On 16 January 1707, after three months of clause-by-clause debate, the Scots Parliament voted decisively by 110 to 67 for union. The ultimate securing of the treaty in the Parliament of Scotland can be attributed to a number of factors.[10] One of the primary motivations in favour of the Union was constitutional. In England, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 that had deposed the Catholic King James II in favour of his Protestant daughter Queen Mary II and her husband William of Orange had been widely welcomed, but in Scotland, it was far more controversial. The Presbyterian majority tended to support King William, while the significant minority of Episcopalians and Catholics tended to support James. The passing of the Claim of Right Act 1689 led to the first of the Jacobite risings, resulting in the Battles of Killiecrankie, Dunkeld and Cromdale.

The Act of Settlement 1701 was, in many ways, a major cause of the Union. The Parliament of Scotland was not happy with the Act of Settlement, as the English Parliament had determined the heir to the throne was Sophia of Hanover, granddaughter of King James VI of Scotland, without formally consulting the Scottish Parliament. In response, the Scottish Parliament passed the Salic Law-based Act of Security in 1704, which gave Scotland the right to choose its own Protestant male successor to the childless Queen Anne.

As a result, the Parliament of England — fearing that at the height of the War of the Spanish Succession, Scotland under a separate, potentially Stuart, monarchy would restore the Auld Alliance with France — decided that, in order to deter any potential French-supported Jacobite invasion of Great Britain, full union of the two Parliaments and nations was essential before Anne's death, and with French military power weakened after the Battle of Blenheim, used a combination of exclusionary legislation (the Alien Act of 1705), diplomacy and bribery to achieve it within three years under the Act of Union 1707. This was in marked contrast to the four attempts at political union between 1606 and 1689, which all failed owing to a lack of political will in both kingdoms. By virtue of Article II of the Treaty of Union, which defined the succession to the British Crown, the Act of Settlement became part of Scots Law as well.

The failure of the Darien scheme, which had effectively bankrupted many people in Scotland and drained the fragile Scottish economy of more than a quarter of its liquid assets, was another major incentive. Many Commissioners had invested heavily in the Company of Scotland and they believed that they would receive compensation for their losses; Article 14 of the Act of Union stipulated that a future Parliament of Great Britain would grant £398,085 10s sterling to Scotland to offset future Scottish liability towards the English national debt. In essence, it was also used as a means of compensation for Scotland's losses in the Darien Scheme.[11] Half of Scotland's trade in the early 1700s was with England, and this, along with the offer of further free trade with England's already extensive overseas colonies, was likely one of the principal reasons the Acts of Union were not as heavily resisted by the government of Scotland as they had with other previous attempts to amalgamate the two countries. Bribery was also prevalent,[10] money was dispatched from England to Scotland for distribution by the Earl of Glasgow. Some of this money was used to hire spies, such as Daniel Defoe.

The Acts of Union were largely unpopular amongst the general population in Scotland.[12] Many petitions were sent to parliament against the union, and there were protests in Edinburgh and several other Scottish towns on the day it was passed, threats of widespread civil unrest resulted in the imposition of martial law. As a result of the unrest in the capital, the signing of the treaty had to be conducted in secrecy.[13] Sir George Lockhart of Carnwath noted that "the whole nation appears against the Union." Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, an ardent pro-unionist, observed that the treaty was "contrary to the inclinations of at least three-fourths of the Kingdom".[14] Many opponents of the Treaty of Union had proposed an alternative to full Parliamentary Union along the lines of other European composite states, such as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Despite this initial opposition, the economic benefits to Scotland from the Union soon became apparent with the beginning of the Scottish Enlightenment, American Tobacco Trade and later growth from the expansion of the British Empire and Industrial Revolution which led to the rapid expansion and industrialisation of Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Scottish home rule

The Visit of King George IV to Scotland in 1822, and subsequent rise in Tartanry, did much to reinvigorate a sense of a specifically Scottish national identity, which had been split between the Episcopalian and Roman Catholic-dominated Highlands and the Presbyterian-dominated Lowlands since the Glorious Revolution in 1688, and continued during the 18th century through the Jacobite risings, the Act of Proscription and subsequent process of Highland Clearances by landlords. From the mid 19th century calls for the devolution of control over Scottish affairs began to be raised, but support for full independence remained limited. The "home rule" movement for a Scottish Assembly was first taken up in 1853 by a body close to the Conservative Party, complaining about the fact that Ireland received more support from the British Government than Scotland and soon began to receive Liberal Party backing,[3] In 1885, the Post of Secretary for Scotland and the Scottish Office were re-established to promote Scotland’s interests and voice its grievances to the British Parliament. In 1886 however, William Ewart Gladstone introduced the Irish Home Rule Bill. When many Scots compared what they had to the Irish offer of Home Rule, this was considered inadequate. It was not an immediate constitutional priority however, especially after the Irish Home Rule Bill was defeated in the House of Commons, and by the time a Scottish home rule bill was first presented to parliament in 1913, its progress, along with the Irish Home Rule Act 1914 was interrupted by World War I and subsequently became overshadowed by the Easter Rising and Irish War of Independence, although the Scottish Office was relocated to St. Andrew's House in Edinburgh during the 1930s.[3][15]

The Scottish National Party itself was formed in 1934 after the union of the National Party of Scotland and the Scottish Party. The SNP did not support all-out independence for Scotland, but rather the establishment of a devolved Scottish Assembly, within the United Kingdom. This became the party's initial position on the constitutional status of Scotland as a result of a compromise between the NPS, who did support independence, and the Scottish Party who were devolutionists. However, the SNP quickly reverted to the original NPS stance of supporting full independence for Scotland. The Interwar period proved difficult years for the SNP, with the rise of undemocratic nationalist forces in Europe in the shape of fascism in Italy and Spain and national socialism in Germany. The alleged similarity between SNP and foreign nationalists, combined with other factors such as a lack of profile in the mainstream media made it difficult for the SNP to grow.[16]

The concept of full independence, or the less controversial home rule, did not re-enter the Scottish mainstream until the 1960s, with the famous Wind of Change speech by Harold Macmillan, which marked the high-point of Decolonisation and the decline of the British Empire, which had already suffered the humiliation of the 1956 Suez Crisis. For many in Scotland, this served to undermine one of the principal raisons d'être of the United Kingdom and also symbolised the end of popular imperialism and imperial unity which had united the prominent Scottish Unionist Party, which subsequently entered a steady decline in support.[17][18] The SNP won a Parliamentary seat in 1967, when Winnie Ewing was the surprise winner of the Hamilton by-election, 1967. This brought the SNP to national prominence, leading to Edward Heath's 1968 Declaration of Perth and the establishment of the Kilbrandon Commission.[19]

1970s resurgence

The discovery of North Sea oil off the east coast of Scotland further invigorated the debate over Scottish independence.[20] The Scottish National Party organised a hugely successful campaign entitled "It's Scotland's oil", emphasising the way in which the discovery of oil could benefit Scotland's then-struggling Deindustrialising economy and its populace.[21] In the February 1974 general election the seven SNP MPs were returned. The failure of the Labour Party to secure an overall majority prompted them to quickly return to the polls. In the subsequent October 1974 election, the SNP performed even better than they had done earlier in the year, winning 11 MPs and managing to garner over 30% of the total vote in Scotland.[22]

In 1974 the Conservative government commissioned the McCrone report, written by professor Gavin McCrone, a leading government economist, to report on the viability of an independent Scotland. He concluded that oil would have given an independent Scotland one of the strongest currencies in Europe. The report went on to say that officials advised government ministers on how to take "the wind out of the SNP sails". Handed over to the incoming Labour administration and classified as secret because of Labour fears over the surge in Scottish National Party popularity, the document only came to light in 2005 when the SNP obtained the report under the Freedom of Information Act 2000.[23][24]

The Labour Party under Harold Wilson had won the election by a tiny majority of only three seats. Following their election to parliament, the SNP MPs pressed for the creation of a Scottish Assembly, which was given added credibility after the conclusions of the Kilbrandon Commission. However, opponents demanded that a referendum be held on the issue. Although the Labour Party and the Scottish National Party both officially supported devolution, support was split in both parties. Labour was divided between those who favoured devolution and those who wanted to maintain a full central Westminster government. In the SNP, there was division between those who saw devolution as a stepping stone to independence and those who feared it might actually distract from that ultimate goal.[20]

The resignation of Harold Wilson brought James Callaghan to power, however its small majority was eroded with several by-election losses and the government became increasingly unpopular during the Winter of Discontent, although an arrangement was negotiated in 1977 with the Liberals known as the Lib-Lab pact and a succession of deals with the Scottish National Party and Plaid Cymru to hold referendums on devolution in exchange for their support, had helped to prolong the government's life.

The result of the referendum in Scotland was a narrow majority in favour of devolution (52% to 48%).[20] However, a condition of the referendum was that 40% of the total electorate should vote in favour in order to make it valid. Thus, with a turnout of 63.6%, only 32.9% had voted "Yes". The Scotland Act 1978 was consequently repealed in March 1979 by a vote of 301-206 in parliament. In the wake of the referendum the supporters of the bill conducted a protest campaign under the slogan "Scotland said yes". They argued that the 40% rule was undemocratic and that the referendum results justified the establishment of the assembly. However, campaigners for a "No" vote countered that voters had been told before the referendum that failing to vote itself was as good as a "No".[25] It was therefore incorrect to conclude that the 36.4% who did not vote, was entirely down to Voter apathy.

In protest, the Scottish National Party MPs withdrew their support from the government. A vote of no confidence was then tabled by the Conservatives and supported by the SNP, the Liberals and Ulster Unionists. It passed by one vote on 28 March 1979, forcing the May 1979 general election, which was won by Margaret Thatcher, effectively ending the Post-war consensus. The then Labour Prime Minister, James Callaghan, famously described this decision by the SNP as that of 'turkeys voting for Christmas'.[26][27] The SNP returned only two MPs in the 1979 election, leading to the formation of the controversial 79 Group within the SNP.

Devolution

Supporters of Scottish independence continued to hold mixed views on the Home Rule movement which included many supporters of union who wanted devolution within the framework of the United Kingdom. Some saw it as a stepping stone to independence, while others wanted to go straight for independence.[28]

In the years of the Conservative government post 1979, the Campaign for a Scottish Assembly was established, eventually publishing the Claim of Right 1989. This then led to the Scottish Constitutional Convention. The convention promoted consensus on devolution on a cross-party basis, though the Conservative Party refused to co-operate and the Scottish National Party withdrew from the discussions when it became clear that the convention was unwilling to discuss Scottish independence as a constitutional option.[20] Arguments against devolution and the Scottish Parliament, levelled mainly by the Conservative Party, were that the Parliament would create a "slippery slope" to Scottish independence, and provide the pro-independence Scottish National Party with a route to government.[29] John Major, the Conservative prime minister before May 1997, campaigned during the 1997 general election on the slogan "72 hours to save the union".[30]

The Labour Party won the 1997 general election and Donald Dewar as Secretary of State for Scotland agreed to the proposals for a Scottish Parliament. A referendum was held in September of that year and 74.3% of those who voted approved the devolution plan (44.87% of the electorate).[31] The Parliament of the United Kingdom subsequently approved the Scotland Act which created an elected Scottish Parliament with control over most domestic policy.[20] In May 1999 Scotland held its first election for a devolved parliament and in July the Scottish Parliament held session for the first time since the previous parliament had been adjourned in 1707.

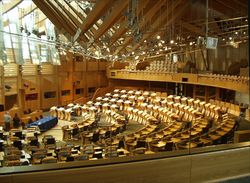

The Scottish Parliament is a unicameral legislature comprising 129 Members, 73 of whom represent individual constituencies and are elected on a first past the post system; 56 are elected in eight different electoral regions by the additional member system, serving for a four year period. The Queen appoints one Member of the Scottish Parliament, (MSP), on the nomination of the Parliament, to be First Minister. Other Ministers are also appointed by the Queen on the nomination of the Parliament and together with the First Minister they make up the Scottish Government, the executive arm of government.[32]

The Labour Party's Donald Dewar became the First Minister of Scotland, while the Scottish National Party became the main opposition party. With the approval of all parties, the egalitarian song "A Man's A Man for A' That", by Robert Burns, was performed at the opening ceremony of the Scottish Parliament.

The Scottish Parliament has legislative authority for all non-reserved matters relating to Scotland, and has limited power to vary income tax, a power it has yet to exercise. The Scottish Parliament can refer devolved matters back to Westminster to be considered as part of United Kingdom-wide legislation by passing a Legislative Consent Motion if United Kingdom-wide legislation is considered to be more appropriate for certain issues. The programmes of legislation enacted by the Scottish Parliament since 1999 have seen a divergence in the provision of public services compared to the rest of the United Kingdom. For instance, the costs of a university education, and care services for the elderly are free at point of use in Scotland, while fees are paid in the rest of the UK. Scotland was the first country in the UK to ban smoking in enclosed public places.[33]

Scotland is also represented in the British House of Commons by 59 MPs elected from territory-based Scottish constituencies.

SNP Government

In the 2007 Scottish Parliament election the Scottish National Party became the single largest party by a margin of one.[34] Lacking an overall majority, the Scottish National Party formed a minority government, installing leader Alex Salmond as First Minister of Scotland.

Proposed referendum

The SNP had a manifesto commitment of holding an independence referendum by 2010.[35][36] After winning the 2007 election, the SNP-controlled Scottish Government published a White Paper entitled Choosing Scotland's Future, which outlines options for the future of Scotland, including independence.[37][38] However, in September 2010 the Scottish Government announced that no referendum would occur before the 2011 elections.[39]

At the time Scottish Labour, the Scottish Conservatives and Scottish Liberal Democrats opposed a referendum offering independence as an option. The former Prime Minister Gordon Brown has also publicly attacked the independence option.[40] Based on a subsequent debate in the Scottish Parliament,[41] the three main parties opposed to independence formed the Calman Commission.[42][43] This will review devolution and consider all constitutional options bar independence.[44]

However, Wendy Alexander had been seen as straying from the established anti-referendum position held by Labour while she was the leader of the Scottish Labour group of MSPs. In May 2008 she called for an independence referendum within 12 months, saying the SNP should have the "courage of its convictions".[45] In a subsequent Prime Minister's Questions time, Gordon Brown denied that Alexander's statement was intended to contradict party policy.[46] Alexander's words also caused concern amongst the other founders of the Calman Commission.[47] In response to Alexander, SNP First Minister Alex Salmond told the Scottish Parliament that he would be sticking to the SNP manifesto commitment of a 2010 referendum.[48] Alexander's resignation as leader of the Labour MSPs (as a result of a controversy over illegal donations [1]) ultimately saw Labour's position reversed again, and her successor Iain Gray reverted to Labour's previous policy of opposing any referendum.[2]

Tavish Scott, the new leader of the Scottish Liberal Democrats, said after being elected that he might consider backing a multi-option referendum with independence as one choice.[49]

In August 2009 the SNP announced that a 2010 Referendum Bill would be part of its third legislative programme for 2009-10, which would detail the question and conduct of a possible referendum on the issue of independence. The Bill was to be published on 25 January 2010, Burns Night, with the referendum proposed for on or around 30 November 2010, St. Andrew's Day. The Bill was not however expected to be passed, due to the SNP's status as a minority government, and the opposition of all the major parties in the Parliament.[50][51]

Legality

A referendum for Scottish independence or a bill of the Scottish Parliament seeking to change the constitutional status of Scotland would not be legally binding on the UK Government because the United Kingdom parliament holds absolute parliamentary sovereignty[52][53] and any changes to the constitutional status are one of the reserved matters for Westminster.[54][55][56] This would mean that at any time Westminster could amend the Scotland Act, changing the powers of the Scottish Parliament and allowing Westminster to legally block any bill for independence brought by the Scottish Government. Westminster has previously amended the Scotland Act to maintain the number of MSPs, which would otherwise have been reduced in line with the reduction of Scottish MPs in the 2005 UK general election.

The legality of any UK component country attaining de facto independence (in the same manner as the origins of the Irish Republic) or declaring unilateral independence outside the framework of UK constitutional convention is uncertain. Prevailing legal opinion following the precedent set by the Supreme Court of Canada's decision on what steps Quebec would need to take to secede is that Scotland would be unable to unilaterally declare independence under international law if the UK government permitted a referendum on an unambiguous question on secession.[57][58] It is uncertain how the unilateral 2008 Kosovo declaration of independence and subsequent recognition by the UK and some EU member states has affected this legal position,[59][60] Former British Prime Ministers John Major and Margaret Thatcher, have recognised a right of the Scottish people to determine their own future.[61] Former Prime Minister James Callaghan rejected the suggestion that Scottish independence could be brought about by a referendum of the Scottish people alone, stating that it ought only to come about if put to a referendum of the British people as a whole.[62]

Support for independence

Nationalism

The Scots National League formed in 1921 as a body primarily based in London seeking Scottish independence, largely influenced by Sinn Féin. They established the Scots Independent newspaper in 1926 and in 1928 they helped the Glasgow University Scottish Nationalist Association form the National Party of Scotland, aiming at a separate Scottish state. One of the founders was Hugh MacDiarmid, a poet who had begun promoting a Scottish literature, while others had Labour Party links.

They cooperated with the Scottish Party, a home rule organisation formed in 1932 by former members of the Conservative Party, and in 1934 they merged to form the Scottish National Party which at first supported only home rule, but then changed to supporting independence. They suffered a setback in the 1930s when the name of nationalism became associated with the National Socialists in Germany, however Scottish nationalism is based on civic nationalism rather than ethnic or ultra-nationalism.[63] The SNP enjoyed a number of election successes in the 1960s, and the discovery of North Sea oil in the 1970s countered concerns about the economic viability of an independent Scotland.[21] The discovery of North Sea oil and the subsequent revenues that went to the United Kingdom treasury have been argued to have benefited Scotland little, with some estimates suggesting over £200 billion of revenue have been amassed thus far. There are also a number of other organisations with a primarily nationalist ideological orientation, from Siol nan Gaidheal, which seeks to revitalise the independence movement through primarily cultural means, to the militant Scottish National Liberation Army.

Republicanism

The independence movement is a disparate one that covers varied political standpoints. While many are republican, this is not Scottish National Party policy. The SNP styles itself as an inclusive institution, subordinating ideological tensions to the primary goal of securing independence. Many nationalists, including Alex Salmond, personally support the retention of the current Monarch - who herself is half-Scottish, through her mother, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon - with Scotland becoming a Commonwealth Realm, similar to Canada or Australia, should independence occur. This would effectively return Scotland to its previous constitutional state of dynastic union, after the Union of the Crowns in 1603. Proportional representation has led to the election to the Scottish Parliament of smaller parties with various political positions but which have independence as a goal; in the 2003 Scottish Parliament election the gains made by the Scottish Green Party and the Scottish Socialist Party boosted the number of pro-independence MSPs. The Scottish Socialist Party has led republican protests and authored the Declaration of Calton Hill, calling for an independent republic.[64]

Self-determination

A number of cross party groupings have been established with the aim of widening the scope of the pro-independence viewpoint and campaigning for a referendum on the issue. The most significant being the Independence Convention which seeks "Firstly, to create a forum for those of all political persuasions and none who support independence; and secondly, to be a national catalyst for Scottish independence."[65] Another being Independence First, a pro-referendum pressure group which has organised public demonstrations.

Political parties

Scottish independence is supported most prominently by the Scottish National Party, but other parties also have pro-independence policies. Those who have had elected representatives in either the Scottish Parliament or local councils in recent years are the Scottish Green Party, the Scottish Socialist Party and Solidarity.

Fifty of the seats in the Scottish Parliament are held by pro-independence members, nearly 40% of the total. This comprises 47 Scottish National Party members, two Green members and Margo MacDonald, an independent politician.

Opposition

There is also a mainstream body of opinion opposed to Scottish independence and in favour of the continuation of the union with England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. This has never emerged as a homogeneous movement, but rather represents a general consensus of the main British political parties and other prominent commentators. Within the Scottish Parliament, the Union is supported by the Scottish Labour Party, Scottish Conservative Party and Scottish Liberal Democrats. Since the 2007 election, these parties collectively hold 79 of the 129 seats, over 60% of the Parliament. Opposition to Scottish independence is also held by many individual figures such as George Galloway and smaller political parties such as the Scottish Unionist Party and the UKIP. It is a broad viewpoint that ranges from those in support of the United Kingdom as a centralised unitary state governed exclusively by the Parliament of the United Kingdom, to those who support varying degrees of devolved transfer of administrative and legislative responsibilities from Westminster to Holyrood, including those who support a solution to the controversial West Lothian question, such as federalism, similar to Germany, Canada or the United States.

Opponents of independence argue that the economy of Scotland has performed well in recent years, with consistent economic growth,[66] urban regeneration,[67] a growing population,[68] historically low unemployment rates,[69] Edinburgh's position as Europe's fifth largest financial centre[70] and Scottish GDP per capita being the largest of any part of the United Kingdom after Greater London and South East England.[71] As a result of this, opponents of independence believe Scotland is economically stronger as a part of the UK economy, and that a country as relatively small as Scotland is comparatively better able to prosper in an increasingly globalised world with the international influence and stability derived from being part of an economically powerful state.[72] Many opponents of independence have also contested claims by the SNP that Scotland currently underperforms economically, relative to other small countries in the region; such as Norway, Finland and Ireland.[73]

David Maddox, writing for The Scotsman claims Scotland's levels of public spending (higher in relation to the rest of the UK[72]) would be difficult to sustain after independence, without raising taxes, as North Sea oil revenues will decline in the longer-term[74]. Others argue that a culture of maintaining a comparatively large public sector and welfare state in Scotland is also an impediment to more substantial and competitive economic growth seen in other nations like Ireland, and that the surplus oil revenue ought to have been invested in a sovereign wealth fund like The Government Pension Fund of Norway. Some wish to reduce public spending and devolve more fiscal powers to the Scottish Parliament in order to address this issue within the broader framework of the Union.[75][76][77]

Francis Tusa, the editor of Defence Analysis and John Park, a Labour MSP have suggested that shipwrighting in an independent Scotland would be jeopardised because UK government contracts currently given to Scottish shipyards would be lost.[78]

Another argument in favour of a continued union is that as part of a unitary British state, Scotland has more influence on international affairs and diplomacy, both politically and militarily, as part of NATO, the G8 and as a permanent member of the UN Security Council.

Those within Scotland who oppose further integration of the European Union claim that independence within Europe outside the EU three would, paradoxically, mean that Scotland would be more marginalised, as a relatively small independent country applying to join the EU, Scotland would be unable to resist the whims and demands of larger member nations, such as being obliged to adopt the Euro and have no greater influence over the formation of treaties like the Common Fisheries Policy,[79] and as a result would be even more politically "impotent" with the resulting loss of its current political influence within the UK Government, which has been claimed by some to be so significant that it has been occasionally dubbed as the "Scottish raj".[80]

Bruce Anderson, writing for the Independent gives the view that a desire for independence is symptomatic of the so-called parochial "Scottish cringe" and assert that some nationalists are bigoted or Anglophobic chauvinists in their attitude towards England.[81] As a result, many unionists emphasise the historical and contemporary cultural ties between Scotland and the rest of the UK, from the Reformation and Union of Crowns, to Scottish involvement in the growth and development of the British Empire and contribution of the Scottish Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution, to a shared solidarity during the Battle of Britain to shared contemporary popular culture, primarily through the prevalence of the English language and a shared currency, to the current demographics, where almost half of the Scottish population have relatives in England, almost a million Scots living and working in England and 400,000 Anglo-Scots now living in Scotland[82]. There are also significant economic links with the Scottish military-industrial complex[83] as well as close links between the Scottish financial sector and Global London-based financial institutions, such as the London Stock Exchange.[84]

Public opinion

Despite the large number of opinion polls conducted on the issue, it is difficult to gauge accurately Scottish public opinion on independence because of the often widely varying results of the polls. Poll results often differ wildly depending on the wording of the question, with the terms such as "break up" and "separation" often provoking a negative response. For example, an opinion poll published by The Scotsman newspaper in November 2006 revealed that a "Majority of Scots now favour independence".[85] However, a poll conducted by Channel 4 only two months later reported that "The figure in support of Scottish independence had seemingly dropped".[86] A third poll by The Daily Telegraph claimed that a significant proportion of Britons would accept the breakup of the United Kingdom.[87] Research conducted in early 2007 revealed that Scottish independence was increasingly appealing to younger Scots.[88] In a poll in 2007 commissioned by The Scotsman newspaper it said Scottish independence was at a 10 year low with only 21% of people in support for it. Conversely, a 2008 opinion poll commissioned by the Sunday Herald newspaper, showed that support for independence was 1% higher than for the status quo.[89] When polls give three options, including an option for greater devolution or a new federal settlement, but stopping short of independence, support for independence significantly declines. In a poll by The Times, published in April 2007, given a choice between independence, the status quo, or greater powers for the Scottish Parliament within the United Kingdom, the last option had majority support.[90]

Polls show a consistent support for a referendum, including amongst those who support the continuation of the union. Most opinion polls performed have a figure of in-principle support for a referendum around 70–75%.[91] In March 2009, The Sunday Times published the results of a YouGov survey on Scottish support for independence (mirroring the earlier 2007 poll). Support for a referendum in principle was found to have fallen to 57% of respondents, with 53% of respondents stating they would vote against independence and 33% stating they would support independence. The Times reported that the fall in support for independence was likely linked to economic recession.[92]

In August 2009 a YouGov survey with the Daily Mail asking if Scottish voters would support independence found that; 28% would vote Yes, 57% would vote No, 11% did not know and 5% would not vote.[93]

See also

- Cornish nationalism

- English independence, English nationalism, Devolved English parliament

- Irish nationalism, Irish independence, United Ireland

- Welsh nationalism, Welsh independence

- List of active autonomist and secessionist movements

References

- Murkens, Jo Eric (2002). Scottish Independence: A Practical Guide. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1699-3.

Notes

- ↑ Christopher A Whatley. (2001) Bought and Sold for English Gold: The Union of 1707 (Tuckwell Press, 2001)

- ↑ "Mob unrest and disorder :: Act of Union 1707". Parliament.uk. http://www.parliament.uk/actofunion/06_03_mob.html. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Scottish Referendums". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/politics97/devolution/scotland/briefing/history.shtml. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Robert the Bruce". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/scottishhistory/independence/features_independence_bruce2.shtml. Retrieved 2007-07-06.

- ↑ "The Declaration of Arbroath (English Translation)". University of Edinburgh. http://www.geo.ed.ac.uk/home/scotland/arbroath_english.html. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Willson, David Harris. King James VI & 1. Jonathan Cape Ltd. ISBN 0224605720.

- ↑ Croft, Pauline. King James. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0333613953.

- ↑ David Plant (2007-02-28). "The Settlement of Scotland 1651-60". British-civil-wars.co.uk. http://www.british-civil-wars.co.uk/glossary/settlement-scotland.htm. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "Act of Union is key to Scottish identity". London: The Times. 2005-11-21. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/article592512.ece. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Act of Union 1707". Channel 4. 2007-04-01. http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/M/monarchy/documents/act_of_union.html. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ↑ Lynch (2001) p604-606

- ↑ "Union of the Parliaments 1707". Rampant Scotland. http://www.rampantscotland.com/know/blknow_union.htm. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ↑ "Treaty was signed 'in the female toilets of restaurant'". The Scotsman. 2007-01-16. http://news.scotsman.com/topics.cfm?tid=1525&id=82392007. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ "Chronology of Scottish Politics". alba.org.uk. http://www.alba.org.uk/timeline/to1707.html. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ "Scottish Home Rule". Skyminds.net. http://www.skyminds.net/politics/scottish-politics/scottish-home-rule/. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "History of the Scottish National Party". Scottishindependence.com. http://www.scottishindependence.com/snp_history.htm. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ Gilson, Mike. "Scottish independence". News.scotsman.com. http://news.scotsman.com/topics.cfm?tid=51&id=77422007. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ National identities > The story so far

- ↑ "Scottish Referendums". Bbc.co.uk. 1990-11-30. http://www.bbc.co.uk/politics97/devolution/scotland/briefing/c20scot.shtml. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 "The Devolution Debate This Century". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/politics97/devolution/scotland/briefing/c20scot.shtml. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Russell, Ben; Kelbie, Paul (2007-06-10). "How black gold was hijacked: North sea oil and the betrayal of Scotland". London: The Independent. http://news.independent.co.uk/uk/this_britain/article331945.ece. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ↑ "Regional distribution of seats and percentage vote". psr.keele.ac.uk. http://www.psr.keele.ac.uk/area/uk/ge74b/seats74b.htm. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ "Papers reveal oil fears over SNP". BBC. 2005-09-12. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/4238744.stm. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ↑ "Scottish Economic Planning Department". http://www.oilofscotland.org/mccronereport.pdf.

- ↑ Department of the Official Report (Hansard), House of Commons, Westminster (1996-04-26). "Hansard record of 26 April 1996 : Column 735". Publications.parliament.uk. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm199596/cmhansrd/vo960426/debtext/60426-18.htm. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "BBC report on 1979 election". Bbc.co.uk. 1979-05-03. http://www.bbc.co.uk/election97/background/pastelec/ge79.htm. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ Hansard, House of Commons, 5th series, vol. 965, col. 471.

- ↑ "SNP should return to the honest argument on independence". The Scotsman. 2003-08-23. http://news.scotsman.com/index.cfm?id=944552003. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- ↑ "Breaking the Old Place up". The Economist. 1999-11-04. http://www.economist.com/research/backgrounders/displaystory.cfm?story_id=326221. Retrieved 2006-10-14.

- ↑ "Politics 97". BBC. September 1997. http://www.bbc.co.uk/politics97/background/pastelec/ge97.shtml. Retrieved 2006-10-14.

- ↑ "Scottish Parliament Factsheet 2003". The Electoral Commission. http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/__data/assets/electoral_commission_pdf_file/0015/13272/TheScottishParliament_18312-6142__S__.pdf. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- ↑ "About Scottish Ministers" Scottish Government. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- ↑ BBC Scotland News Online "Scotland begins pub smoking ban", BBC Scotland News, 2006-03-26. Retrieved on 2006-07-17.

- ↑ Wintour, Patrick (2007-05-04). "SNP wins historic victory". London: The Guardian. http://politics.guardian.co.uk/scotland/story/0,,2072912,00.html. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- ↑ At-a-glance: SNP manifesto, BBC News, 12 April 2007.

- ↑ SNP Manifesto (PDF)

- ↑ SNP outlines independence plans, BBC News, 14 August 2007

- ↑ http://www.scotland.gov.uk/topics/a-national-conversation

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-11196967

- ↑ "UK | Scots split would harm UK - Brown". BBC News. 2006-11-25. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/6182762.stm. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "The Scottish Parliament - Official Report". Scottish.parliament.uk. http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/business/officialReports/meetingsParliament/or-07/sor1206-02.htm#Col4133. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "Commission on Scottish Devolution". Commission on Scottish Devolution. http://www.commissiononscottishdevolution.org.uk/. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "Scotland | Devolution body members announced". BBC News. 2008-04-28. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/7371693.stm. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ Calman devolution commission revealed, The Herald, April 28, 2008.

- ↑ 'Bring on' referendum - Alexander, BBC News, 4 May 2008.

- ↑ Wendy Alexander isolated in breakaway vote crisis, The Times, May 8, 2008.

- ↑ 'Concern' over referendum shift, BBC News, 9 May 2008.

- ↑ Sparrow, Jason. Cameron accuses Brown of losing control as Scotland row rages on, The Guardian, May 8, 2008.

- ↑ Carrell, Severin. Scottish independence: Lib Dems offer possibility of referendum support, The Guardian, August 26, 2008.

- ↑ "Referendum Bill". Oficial website, About > Programme for Government > 2009-10 > Summaries of Bills > Referendum Bill. Scottish Government. 2009-09-02. Archived from the original on 2009-09-10. http://www.webcitation.org/5jggEjHoR. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ↑ "Salmond to push ahead with referendum Bill". London: The Times. 2009-09-03. Archived from the original on 2009-09-10. http://www.webcitation.org/5jgoTKBiL. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ↑ http://www.parliament.uk/commons/lib/research/rp2003/rp03-084.pdf

- ↑ "UK Parliament - Parliamentary sovereignty". Parliament.uk. 2007-11-21. http://www.parliament.uk/about/how/laws/sovereignty.cfm. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "Scotland Act 1998 (c. 46)". Opsi.gov.uk. 1998-11-19. http://www.opsi.gov.uk/Acts/acts1998/ukpga_19980046_en_1. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118772717/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0

- ↑ "A Real Scottish Parliament". Scottishpolitics.org. http://www.scottishpolitics.org/devolution/realparliament.html. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/pss/1096974

- ↑ "Scotland and the thorny road to independence". London: Times Online. 2007-01-18. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/letters/article1293929.ece. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "Search - Global Edition - The New York Times". International Herald Tribune. 2009-03-29. http://www.iht.com/articles/ap/2008/02/15/europe/EU-GEN-Republic-of-Wherever.php. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "Kosovan Independence". Craig Murray. http://www.craigmurray.org.uk/archives/2008/02/kosovan_indepen.html. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ Hazell, Robert. Rites of secession, The Guardian, July 29, 2008.

- ↑ http://www.heraldscotland.com/callaghan-vetoed-referendum-on-uk-break-up-1.828292

- ↑ "Multiculturalism and Scottish nationalism". Commission for Racial Equality. http://www.cre.gov.uk/publs/connections/04sp_scotland.html. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ Martin, Lorna (2004-10-10). "Holyrood survives birth pains". London: Guardian Unlimited. http://observer.guardian.co.uk/politics/story/0,,1323939,00.html. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ "Introduction: Aims and Questions". Scottish Independence Convention. http://www.scottishindependenceconvention.com/Introduction.asp. Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- ↑ Scotland &mdsah; competing with the world

- ↑ "The Cities Are Back". Glasgow-edinburgh.co.uk. http://www.glasgow-edinburgh.co.uk/?page_id=24. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "Population rises for fourth year". BBC News. 2007-04-26. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/6595431.stm. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "Scots unemployment at record low". BBC News. 2004-02-11. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/3479209.stm. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ "Economics in Scotland". Sgpe.ac.uk. http://www.sgpe.ac.uk/economics/finance.htm. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ http://www.bized.co.uk/current/leisure/2004_5/300505.htm

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 "The Scottish gamble". BBC News. 2007-04-30. http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/thereporters/evandavis/2007/04/the_scottish_gamble_1.html. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- ↑ "How Scotland really compares with Ireland, Norway and Finland" (PDF). Jim Devine MP. 2007-12-21. http://www.jimdevine.org.uk/EZEdit/popups/uploads/How%20Scotland%20really%20compares%20with%20Ireland%20Norway.pdf. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- ↑ "Oil price fuels fresh row on Scots 'deficit'". The Scotsman. 2008-06-21. http://news.scotsman.com/latestnews/Oil-price-fuels-fresh-row.4209389.jp. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ↑ "Study finds no benefit in fiscal autonomy as McCrone calls time on Barnett". The Scotsman. 2007-01-26. http://news.scotsman.com/topics.cfm?tid=447&id=134592007. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- ↑ "'Billions needed' to boost growth". BBC News. 2006-03-14. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/4803758.stm. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- ↑ "Public/private sectors in economy need to be rebalanced". The Scotsman. 2006-03-15. http://news.scotsman.com/opinion.cfm?id=385272006. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- ↑ "Doubts raised over future of shipyards under independence". The Scotsman. 2007-07-27. http://news.scotsman.com/latestnews/Doubts-raised-over-future-of.3310480.jp. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ↑ "Scottish Independence - Reality or Illusion?". Global Politician. 2007-01-05. http://www.globalpolitician.com/articledes.asp?ID=2725&cid=3&sid=74. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- ↑ "Scots urged to raise their profile". BBC. 2001-09-22. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/in_depth/uk_politics/2001/conferences_2001/snp/1556912.stm. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- ↑ "The sullen self-pity of Anglophobic Scots". London: The Independent. 2006-11-27. http://comment.independent.co.uk/columnists_a_l/bruce_anderson/article2018684.ece. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ "The Union Jocks". Scotland on Sunday. 2008-02-17. http://scotlandonsunday.scotsman.com/opinion/The-Union-Jocks.3786184.jp. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ↑ "Doubts raised over future of shipyards under independence". The Scotsman. 2007-07-27. http://news.scotsman.com/scotland.cfm?id=1171132007. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ↑ "Scots and English flourish in the Union". London: The Telegraph. 2001-04-11. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/opinion/main.jhtml;?xml=/opinion/2007/04/11/do1101.xml. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- ↑ "Vital gains forecast for SNP in swing from Labour". The Scotsman. 2006-11-01. http://news.scotsman.com/topics.cfm?tid=324&id=1615112006. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ↑ "Do the Scots support independence?". Channel 4. 2007-01-18. http://www.channel4.com/news/articles/politics/domestic_politics/factcheck+do+the+scots+support+independence/251043. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ↑ Hennessy, Patrick; Kite, Melissa (2006-11-27). "Britain wants UK break up, poll shows". London: The Daily Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2006/11/26/nunion26.xml. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ↑ "Younger Scots and Welsh may become more likely to support Nationalist parties". Economic & Social Research Council. 2007-05-04. http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2007-05/esr-ysa050307.php. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ↑ "41% of Scots back the break-up of the union". Sunday Herald. 2008-04-12. http://www.sundayherald.com/news/heraldnews/display.var.2192965.0.41_of_scots_back_the_breakup_of_the_union.php. Retrieved 2008-05-04.

- ↑ "How SNP could win and lose at the same time". London: The Times. 2007-04-20. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/politics/article1680124.ece. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ↑ "Polls on support for independence and for a referendum on independence". Independence First. http://www.independence1st.com/content/polls.shtml. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ↑ Allardyce, Jason (2009-03-15). "Voters ditch SNP over referendum". London: The Times. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/scotland/article5908726.ece. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ↑ http://ukpollingreport.co.uk/blog/scottish-independence

External links

- Pro-independence party websites

- Scottish National Party

- Scottish Green Party

- Scottish Socialist Party

- Solidarity Scotland

- Scottish Democratic Alliance

- Unionist party websites

- Other websites

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||